We find ourselves in a time when, in the West, women make up the majority of any yoga class, and yet as in most fields of study, yet again, the patriarchal systems have ignored or hidden the practices, influences and valuable role of women in Yoga’s past. I am beginning to hear a resounding, collective chorus asking ‘What about the unspoken history of women in Yoga and spiritual practice?’

I teach the history and philosophy modules on the Contemporary Yoga Teacher Training course, a truly wonderful programme run by my dear colleagues Karla Brodie and Neal Goshal. We delve into both the dual and non-dual philosophical foundations that feed into the Yoga of today and we look at an overview of more than 4000 years of history and it is clear that the role and representation of women has been lost, obscured and ignored. This is a huge topic, too much for a blog really, but as a feminist I want to acknowledge this here on my websire and highlight some writers and sources that open up some of this lost history. I hope it inspires you to study more about this and reflect upon how it affects how and what you practice.

In her book, Yoni Shakti, Uma Dinsmore-Tuli, invites us to consider the possibility that the inspiration for the earliest genesis of Yoga may be rooted in a quest to emulate the encounters of female powers such as birth and menstruation. It seems that the experiences of the female body that were initially celebrated and included in the shamanaistic ritual space were cast out as patriarchal systems developed and by the time Vedic times came along, women, especially menstruating ones, were banished from ritual space.

The Vedas were some of the earliest texts in history and so it is interesting to note that these times mark the introduction of literacy and the alphabet. One of my Tantric teachers, Anne Douglas, suggests that there was a rewiring of the brain over this time as goddess culture shifted from imagery to word and there was an upset to the balance between the masculine and the feminine. One can speculate that Tantra developed later on partly in response to the misogynist shut down of women and access to spiritual knowledge. With the Tantras there is a more transgressive approach and return to appreciating the feminine Siddhis (powers) through visualisations and meditations on the various goddesses, including those represented through Yantras. Women were included in some practices and there are some female gurus whose teachings have been recorded including that of the Tantric mystic and poetess from fourteenth-century Kashmir known as Lalleshwari (or Lal Ded). Her exquisite poetic sayings (vākh) show a deep felt sense of the non-dual practice:

Enlightenment absorbs this universe of qualities.

When that merging occurs, there is nothing

but God. This is the only doctrine.

There is no word for it, no mind

to understand it with, no categories

of transcendence or non-transcendence,

no vow of silence, no mystical attitude.

There is no Shiva and no Shakti

in enlightenment, and if there is something

that remains, that whatever-it-is

is the only teaching.

What a mesmerising description of Enlightenment! However it seems that many of the Tantric teachings including those of the non-dual Kashmiri Shaivism tradition were still mostly delivered via men.

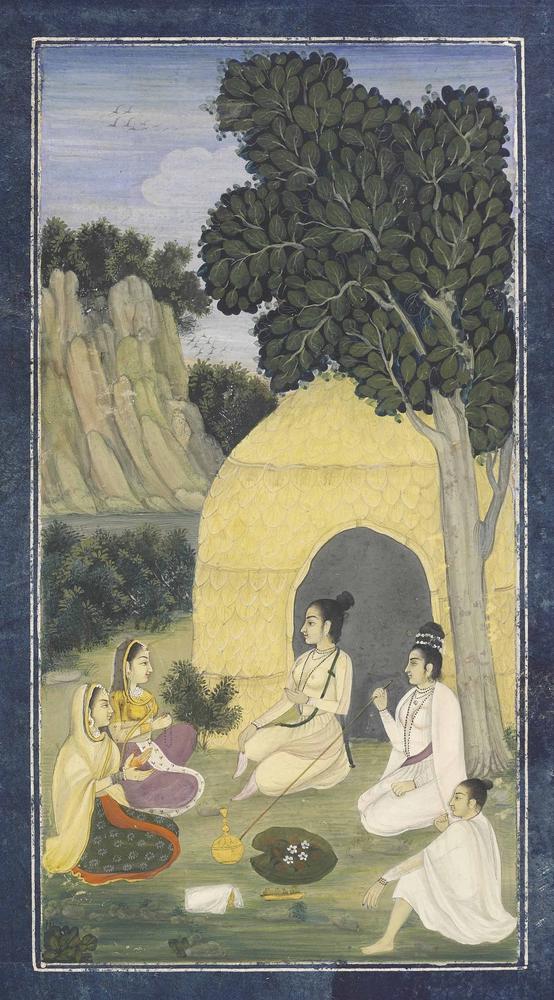

Hatha Yoga was even more male centric. There may have been some female practitioners but the lack of records and texts that speak to the Women’s sadhana makes academic study hard in this area. Ruth Westoby is a practitioner/scholar researching the role of women in Yoga. She confirms that women appear infrequently in Hatha texts, and it is rare to find any specific references but those who preserve their rajas are said to be true yoginis! What preserving Rajas actually means for a woman is somewhat confusing but may result in the halting of menstruation. She offers a couple of online courses that delve into the interpretative strategies that we can use to tell herstory and highlights that a chronology of female practitioners must be described through more than just texts but through “stone, art and word”. In other words, we need to carefully assess visual and material evidence to look for the role of women in spiritual practice.As the academic field of yoga opens up and includes collecting more resources and evidence, we see that there is far more that has yet to be uncovered than what we currently know through the male dominated historical and academic perspective.

There are a number of femininst historians searching for the herstory of Yoga including Wendy Donigar, the American Indologist who has written many books including The Hindus: An Alternative History. She highlights an alternative narrative to the one constituted by the most famous texts in Sanskrit and tells the stories of the others —the people who, from the standpoint of most high-caste Hindu males, are alternative in the sense of otherness, people of other religions, or cultures, or castes, or species (animals), or gender (women). She shows how women, Pariahs (oppressed castes, sometimes called Untouchables)—did actually contribute to Hinduism. She says:

“I hope to bring in more actors, and more stories, upon the stage, to show the presence of brilliant and creative thinkers entirely off the track beaten by Brahmin Sanskritists and of diverse voices that slipped through the filter, and, indeed, to show that the filter itself was quite diverse, for there were many different sorts of Brahmins; some whispered into the ears of kings, but others were dirt poor and begged for their food every day.”

She has inspired many others to study and consider a feminist perspective including Laura Amazzone, who is an author, teacher and Yogini who completed her master’s degree in philosophy and religion, with an emphasis in women’s spirituality at the California Institute of Integral Studies. One of her books, Goddess Durga and Sacred Female Power explores the millennia-old rituals and manifestations of the Goddess in South Asia and honours female creative & sexual power as a divine force. She is fascinated by the Goddess temples and writes about Yoginis past and present which you can also read about in this fascinating article:http://www.sutrajournal.com/yoginis-of-past-and-present-by-laura-amazzone

Vicki Noble is another author who has written extensively on these issues, relating not just to Indian culture but the world-wide roots of matriarchy and the repression of it. She explains that matriarchy (matri/mother and arche/beginning) can best be understood, not as female dominance, but literally as a form of social organization that “begins with the mother.” Physical anthropology suggests that these matricentric beginnings go all the way back to our origins as a human species.

“Rather like the image of a woman pregnant with boy and girl twins, matriarchy represents an egalitarian social structure in which everyone comes from one Great Mother and gender is differentiated, yet not dualistic or polarized. Women in matriarchal societies do not rule in the reverse sense of patriarchy, but the maternal principle is the governing force. Like women in Matriarchy, the men also thrive in these mother-centred communities.”

These are just some of the academics and artists who are working to change the narrative and help us understand our Yoga practice from a more authentic and inclusive perspective, honouring women and their wisdom bodies as a source and upholding of the ancient teachings.

What questions does this raise for you and how might it inspire or change the way you practice Yoga whatever gender you identify as?